Living American Art Collotype No 78 Reproduced by Courtesy of Bartlett Arkell

A museum ( mew-ZEE-əm; plural museums or, rarely, musea) is a building or establishment that cares for and displays a drove of artifacts and other objects of artistic, cultural, historical, or scientific importance.[1] Many public museums make these items bachelor for public viewing through exhibits that may exist permanent or temporary.[2] The largest museums are located in major cities throughout the globe, while thousands of local museums exist in smaller cities, towns, and rural areas. Museums take varying aims, ranging from the conservation and documentation of their collection, serving researchers and specialists to catering to the general public. The goal of serving researchers is not only scientific, but intended to serve the general public.

There are many types of museums, including art museums, natural history museums, science museums, war museums, and children's museums. According to the International Quango of Museums (ICOM), there are more than than 55,000 museums in 202 countries.[3]

Etymology [edit]

The English "museum" comes from the Latin word, and is pluralized as "museums" (or rarely, "musea"). Information technology is originally from the Aboriginal Greek Μουσεῖον (Mouseion), which denotes a identify or temple dedicated to the muses (the patron divinities in Greek mythology of the arts), and hence was a edifice gear up apart for study and the arts,[four] especially the Musaeum (institute) for philosophy and enquiry at Alexandria, built under Ptolemy I Soter about 280 BC.[5]

Purpose [edit]

The purpose of modern museums is to collect, preserve, interpret, and display objects of artistic, cultural, or scientific significance for the written report and pedagogy of the public. From a visitor or community perspective, this purpose tin can likewise depend on ane's point of view. A trip to a local history museum or large city fine art museum can be an entertaining and enlightening way to spend the day. To metropolis leaders, an active museum community can be seen as a gauge of the cultural or economic health of a metropolis, and a way to increase the sophistication of its inhabitants. To a museum professional, a museum might be seen every bit a way to brainwash the public about the museum'due south mission, such every bit ceremonious rights or environmentalism. Museums are, to a higher place all, storehouses of cognition.[ commendation needed ] In 1829, James Smithson'south bequest, that would fund the Smithsonian Establishment, stated he wanted to establish an institution "for the increase and diffusion of knowledge".[6]

Museums of natural history in the late 19th century exemplified the scientific desire for classification and for interpretations of the world. Gathering all examples for each field of cognition for research and display was the purpose. As American colleges grew in the 19th century, they adult their own natural history collections for the use of their students. By the last quarter of the 19th century, scientific research in universities was shifting toward biological enquiry on a cellular level, and cutting-border research moved from museums to university laboratories.[7] While many big museums, such every bit the Smithsonian Institution, are still respected every bit research centers, enquiry is no longer a main purpose of most museums. While there is an ongoing contend about the purposes of interpretation of a museum's collection, there has been a consistent mission to protect and preserve cultural artifacts for future generations. Much care, expertise, and expense is invested in preservation efforts to retard decomposition in aging documents, artifacts, artworks, and buildings. All museums display objects that are important to a culture. As historian Steven Conn writes, "To encounter the matter itself, with ane'due south own eyes and in a public place, surrounded past other people having some version of the aforementioned experience, can exist enchanting."[eight]

Museum purposes vary from institution to institution. Some favor education over conservation, or vice versa. For case, in the 1970s, the Canada Science and Technology Museum favored education over preservation of their objects. They displayed objects too as their functions. One exhibit featured a historical printing press that a staff member used for visitors to create museum memorabilia.[9] Some museums seek to reach a wide audition, such equally a national or state museum, while others have specific audiences, similar the LDS Church History Museum or local history organizations. Generally speaking, museums collect objects of significance that comply with their mission statement for conservation and display.

Although most museums do not allow physical contact with the associated artifacts, there are some that are interactive and encourage a more hands-on approach. In 2009, Hampton Courtroom Palace, a palace of Henry VIII, in England opened the council room to the general public to create an interactive environment for visitors. Rather than allowing visitors to handle 500-year-old objects, however, the museum created replicas, likewise as replica costumes. The daily activities, historic wearable, and even temperature changes immerse the visitor in an impression of what Tudor life may have been.[10]

Definitions by major museum professional organizations [edit]

Major museum professional person organizations from around the world offer some definitions every bit to what a museum is and their purpose. Common themes in all the definitions are public good and care, preservation, and estimation of collections.

The International Council of Museums' current definition of a museum (adopted in 1970): "A museum is a non-turn a profit, permanent institution in the service of social club and its development, open to the public, which acquires, conserves, researches, communicates and exhibits the tangible and intangible heritage of humanity and its environment for the purposes of education, study, and enjoyment."[eleven]

A proposed change to this definition, which would accept museums actively appoint with political and social issues, was postponed in 2020 after substantial opposition from ICOM members.[12]

The Canadian Museums Association's definition: "A museum is a non-turn a profit, permanent institution, that does not exist primarily for the purpose of conducting temporary exhibitions and that is open to the public during regular hours and administered in the public interest for the purpose of conserving, preserving, studying, interpreting, assembling and exhibiting to the public for the instruction and enjoyment of the public, objects and specimens or educational and cultural value including artistic, scientific, historical and technological material."[13]

The United kingdom'south Museums Association's definition: "Museums enable people to explore collections for inspiration, learning and enjoyment. They are institutions that collect, safeguard and make accessible artifacts and specimens, which they hold in trust for society."

While the American Alliance of Museums does not take a definition their listing of accreditation criteria to participate in their Accreditation Program states a museum must: "Be a legally organized nonprofit institution or function of a nonprofit organization or government entity; Be essentially educational in nature; Take a formally stated and approved mission; Utilize and interpret objects or a site for the public presentation of regularly scheduled programs and exhibits; Have a formal and appropriate program of documentation, care, and use of collections or objects; Deport out the to a higher place functions primarily at a physical facility or site; Have been open up to the public for at least two years; Be open to the public at least 1,000 hours a year; Have accessioned lxxx per centum of its permanent collection; Take at least one paid professional staff with museum cognition and experience; Have a total-time managing director to whom authority is delegated for mean solar day-to-twenty-four hour period operations; Have the financial resources sufficient to operate effectively; Demonstrate that it meets the Core Standards for Museums; Successfully consummate the Cadre Documents Verification Program" [14]

Additionally a there is a legal definition of museum in The states legislation in the authorizing the institution of the Constitute of Museum and Library Services: "Museum means a public, tribal, or individual nonprofit establishment which is organized on a permanent basis for essentially educational, cultural heritage, or aesthetic purposes and which, using a professional staff: Owns or uses tangible objects, either animate or inanimate; Cares for these objects; and Exhibits them to the general public on a regular basis." (Museum Services Human action 1976) [15]

History [edit]

Aboriginal history [edit]

Bel-shalti-nannar's museum label (circa 530 BCE), kickoff museum label known) in city of Ur (mod Tell el-Muqayyar, Iraq

I of the oldest museums known is Ennigaldi-Nanna'due south museum, congenital by Princess Ennigaldi in modernistic Iraq at the terminate of the Neo-Babylonian Empire. The site dates from c. 530 BCE, and independent artifacts from earlier Mesopotamian civilizations. Notably, a dirt drum characterization—written in three languages—was found at the site, referencing the history and discovery of a museum item.[16] [17]

Ancient Greeks and Romans collected and displayed art and objects merely perceived museums differently from modern twenty-four hour period views. In the classical menstruation the museums were the temples and their precincts which housed collections of votive offerings. Paintings and sculptures were displayed in gardens, forums, theaters, and bathhouses.[18] In the aboriginal past there was piffling differentiation between libraries and museums with both occupying the building and were oftentimes connected to a temple or imperial palace. The Museum of Alexandria is believed to be one of the earliest museums in the world. While it connected to the Library of Alexandria information technology is non clear if the museum was in a unlike building from the library or was role of the library complex. While trivial was known about the museum is was an inspiration for museums during the early on Renaissance period.[19] The majestic palaces also functioned as a kind of museum outfitted with art and objects from conquered territories and gifts from ambassadors from other kingdoms allowing the ruler to brandish the amassed collections to guests and to visiting dignitaries.[20]

Too in Alexandria from the time of Ptolemy Ii Philadelphus (r. 285-246 BCE), was the start zoological park. At first used by Philadelphus in an attempt to domesticate African elephants for employ in war, the elephants were also used for show along with a menagerie of other animals specimens including hartebeests, ostriches, zebras, leopards, giraffes, rhinoceros, and pythons.[19] [21]

Early on history [edit]

The old Ashmolean Museum edifice

Early museums began as the private collections of wealthy individuals, families or institutions of art and rare or curious natural objects and artifacts. These were often displayed in and so-called "wonder rooms" or cabinets of curiosities. These contemporary museums first emerged in western Europe, then spread into other parts of the earth.[22]

Public admission to these museums was frequently possible for the "respectable", especially to individual art collections, only at the whim of the possessor and his staff. One mode that aristocracy men during this time period gained a college social condition in the world of elites was by condign a collector of these curious objects and displaying them. Many of the items in these collections were new discoveries and these collectors or naturalists, since many of these people held interest in natural sciences, were eager to obtain them. By putting their collections in a museum and on display, they not only got to show their fantastic finds but also used the museum equally a way to sort and "manage the empirical explosion of materials that wider broadcasting of ancient texts, increased travel, voyages of discovery, and more systematic forms of communication and exchange had produced".[23]

1 of these naturalists and collectors was Ulisse Aldrovandi, whose collection policy of gathering equally many objects and facts nigh them was "encyclopedic" in nature, reminiscent of that of Pliny, the Roman philosopher and naturalist.[24] The thought was to swallow and collect as much knowledge as possible, to put everything they nerveless and everything they knew in these displays. In time, notwithstanding, museum philosophy would change and the encyclopedic nature of data that was and so enjoyed by Aldrovandi and his cohorts would be dismissed too as "the museums that independent this knowledge". The 18th-century scholars of the Age of Enlightenment saw their ideas of the museum as superior and based their natural history museums on "organization and taxonomy" rather than displaying everything in any order after the fashion of Aldrovandi.[25]

The first "public" museums were often attainable simply by the center and upper classes. It could be hard to proceeds entrance. When the British Museum opened to the public in 1759, it was a concern that big crowds could impairment the artifacts. Prospective visitors to the British Museum had to apply in writing for admission, and small groups were immune into the galleries each day.[26] The British Museum became increasingly pop during the 19th century, amongst all historic period groups and social classes who visited the British Museum, specially on public holidays.[27]

The Ashmolean Museum, however, founded in 1677 from the personal collection of Elias Ashmole, was set up in the University of Oxford to be open to the public and is considered by some to be the first modern public museum.[28] The drove included that of Elias Ashmole which he had collected himself, including objects he had caused from the gardeners, travellers and collectors John Tradescant the elder and his son of the same name. The drove included antique coins, books, engravings, geological specimens, and zoological specimens—one of which was the stuffed body of the terminal dodo ever seen in Europe; but by 1755 the stuffed dullard was and then moth-eaten that it was destroyed, except for its head and one claw. The museum opened on 24 May 1683, with naturalist Robert Plot as the first keeper. The first edifice, which became known equally the Old Ashmolean, is sometimes attributed to Sir Christopher Wren or Thomas Forest.[29]

The Louvre museum in 1853.

In France, the beginning public museum was the Louvre Museum in Paris,[30] opened in 1793 during the French Revolution, which enabled for the first time gratis admission to the former French royal collections for people of all stations and condition. The fabled art treasures collected by the French monarchy over centuries were attainable to the public iii days each "décade" (the 10-day unit which had replaced the week in the French Republican Calendar). The Conservatoire du muséum national des Arts (National Museum of Arts's Conservatory) was charged with organizing the Louvre as a national public museum and the centerpiece of a planned national museum system. Every bit Napoléon I conquered the great cities of Europe, confiscating art objects every bit he went, the collections grew and the organizational task became more and more complicated. Afterwards Napoleon was defeated in 1815, many of the treasures he had amassed were gradually returned to their owners (and many were non). His plan was never fully realized, but his concept of a museum as an agent of nationalistic fervor had a profound influence throughout Europe.

Chinese and Japanese visitors to Europe were fascinated past the museums they saw there, but had cultural difficulties in grasping their purpose and finding an equivalent Chinese or Japanese term for them. Chinese visitors in the early 19th century named these museums based on what they independent, so defined them as "os amassing buildings" or "courtyards of treasures" or "painting pavilions" or "curio stores" or "halls of military feats" or "gardens of everything". Nippon first encountered Western museum institutions when information technology participated in Europe'south World's Fairs in the 1860s. The British Museum was described by one of their delegates as a 'hakubutsukan', a 'house of extensive things' – this would somewhen become accepted every bit the equivalent word for 'museum' in Japan and People's republic of china.[31]

Mod history [edit]

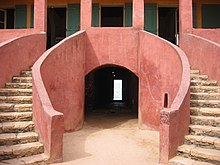

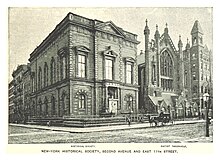

New-York Historical Society. Building erected in 1855-57 and served as the Club'south dwelling house until 1908

American museums eventually joined European museums as the world'southward leading centers for the production of new knowledge in their fields of involvement. A period of intense museum building, in both an intellectual and physical sense was realized in the late 19th and early on 20th centuries (this is oft called "The Museum Flow" or "The Museum Age"). While many American museums, both natural history museums and fine art museums alike, were founded with the intention of focusing on the scientific discoveries and creative developments in Due north America, many moved to emulate their European counterparts in certain means (including the evolution of Classical collections from ancient Arab republic of egypt, Hellenic republic, Mesopotamia, and Rome). Drawing on Michel Foucault's concept of liberal government, Tony Bennett has suggested the development of more modern 19th-century museums was role of new strategies past Western governments to produce a citizenry that, rather than be directed by coercive or external forces, monitored and regulated its own conduct. To comprise the masses in this strategy, the private space of museums that previously had been restricted and socially sectional were made public. As such, objects and artifacts, particularly those related to high culture, became instruments for these "new tasks of social management".[32] Universities became the primary centers for innovative research in the United States well before the start of World War II. Notwithstanding, museums to this solar day contribute new noesis to their fields and proceed to build collections that are useful for both research and display.[ citation needed ]

Exhibiting human remains of Native Americans.

The belatedly twentieth century witnessed intense debate concerning the repatriation of religious, indigenous, and cultural artifacts housed in museum collections. In the United States, several Native American tribes and advancement groups have lobbied extensively for the repatriation of sacred objects and the reburial of human remains.[33] In 1990, Congress passed the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), which required federal agencies and federally funded institutions to repatriate Native American "cultural items" to culturally affiliate tribes and groups.[34] Similarly, many European museum collections often incorporate objects and cultural artifacts acquired through imperialism and colonization. Some historians and scholars have criticized the British Museum for its possession of rare antiquities from Egypt, Greece, and the Middle East.[35]

Management [edit]

Honours lath listing Directors of a Museum.

The roles associated with the management of a museum largely depend on the size of the institution, but every museum has a bureaucracy of governance with a Board of Trustees or Board of Directors serving at the summit. The Director is adjacent in control and works with the Board to establish and fulfill the museum'southward mission statement and to ensure that the museum is accountable to the public.[36] Together, the Lath and the Director establish a system of governance that is guided by policies that gear up standards for the establishment. Documents that ready these standards include an institutional or strategic plan, institutional code of ethics, bylaws, and collections policy. The American Alliance of Museums (AAM) has also formulated a series of standards and best practices that help guide the direction of museums.

- Board of Trustees or Lath of directors – The board governs the museum and is responsible for ensuring the museum is financially and ethically audio. They set standards and policies for the museum. Board members are often involved in fundraising aspects of the museum and represent the institution.[37] Some museum use the terms "directors" and "trustees" interchangeably but both are different legal instruments. A board of directors governs a nonprofit corporation, a lath of trustees is responsible for governing a charitable trust, foundation, or endowment.[38] In the case of small museums and all volunteer museums, a board may be more hands-on in the 24-hour interval-to-day operations of the museum.[39]

- Director- The managing director is the face of the museum to the professional and public customs. They communicate closely with the board to guide and govern the museum. They work with the staff to ensure the museum runs smoothly. According to museum professionals Hugh H. Genoways and Lynne Grand. Republic of ireland, "Assistants of the arrangement requires skill in conflict direction, interpersonal relations, budget management and monitoring, and staff supervision and evaluation. Managers must likewise set legal and ethical standards and maintain involvement in the museum profession."[37]

Curator and exhibit designer dress a mannequin for an showroom.

Restoration of a gilded mirror past Conservator.

Various positions within the museum carry out the policies established by the Board and the Manager. All museum employees should work together toward the museum's institutional goal. Hither is a list of positions normally found at museums:

- Curator – Curators are the intellectual drivers behind exhibits. They research the museum's collection and topic of focus, develop exhibition themes, and publish their research aimed at either a public or academic audience. Larger museums have curators in a diverseness of areas. For case, The Henry Ford has a Curator of Transportation, a Curator of Public Life, a Curator of Decorative Arts, etc. Many fine art museums have curators defended to specific historic periods and geographic regions, such every bit American fine art and modern or contemporary art.[ citation needed ]

- Collections Management – Collections managers are primarily responsible for the hands-on care, motion, and storage of objects. They are responsible for the accessibility of collections and collections policy.

- Registrar – Registrars are the primary record keepers of the collection. They insure that objects are properly accessioned, documented, insured, and, when appropriate, loaned. Ethical and legal issues related to the collection are dealt with past registrars. Along with collections managers, they uphold the museum's collections policy.[ citation needed ]

- Educator – Museum educators are responsible for educating museum audiences. Their duties can include designing tours and public programs for children and adults, teacher training, developing classroom and continuing education resource, customs outreach, and volunteer management.[xl] Educators non only work with the public, but besides interact with other museum staff on exhibition and program development to ensure that exhibits are audience-friendly.

- Exhibit Designer – Exhibit designers are in charge of the layout and concrete installation of exhibits. They create a conceptual design and and so bring information technology to fruition in the physical space.[ citation needed ]

- Conservator – Conservators focus on object restoration. More preserving the object in its present state, they seek to stabilize and repair artifacts to the condition of an earlier era.[41]

Other positions commonly found at museums include: building operator, public programming staff, photographer, librarian, archivist, groundskeeper, volunteer coordinator, preparator, security staff, development officer, membership officer, business officer, gift shop manager, public relations staff, and graphic designer.

At smaller museums, staff members often fulfill multiple roles. Some of these positions are excluded entirely or may exist carried out by a contractor when necessary.

Protection [edit]

The cultural property stored in museums is threatened in many countries by natural disaster, war, terrorist attacks or other emergencies. To this finish, an internationally important aspect is a strong bundling of existing resources and the networking of existing specialist competencies in order to prevent any loss or damage to cultural property or to keep harm as depression as possible. International partner for museums is UNESCO and Blue Shield International in accord with the Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Holding from 1954 and its 2nd Protocol from 1999. For legal reasons, there are many international collaborations between museums, and the local Blueish Shield organizations.[42] [43]

Bluish Shield has conducted extensive missions to protect museums and cultural assets in armed disharmonize, such as 2011 in Egypt and Great socialist people's libyan arab jamahiriya, 2013 in Syrian arab republic and 2014 in Republic of mali and Republic of iraq. During these operations, the annexation of the drove is to exist prevented in particular.[44]

Planning [edit]

The pattern of museums has evolved throughout history. Yet, museum planning involves planning the actual mission of the museum forth with planning the space that the collection of the museum will be housed in. Intentional museum planning has its ancestry with the museum founder and librarian John Cotton Dana. Dana detailed the procedure of founding the Newark Museum in a series of books in the early 20th century so that other museum founders could program their museums. Dana suggested that potential founders of museums should form a committee first, and achieve out to the community for input every bit to what the museum should supply or do for the customs.[45] According to Dana, museums should be planned according to community's needs:

"The new museum ... does not build on an educational superstition. It examines its community's life showtime, then straightway bends its energies to supplying some the material which that community needs, and to making that material's presence widely known, and to presenting it in such a way as to secure it for the maximum of utilise and the maximum efficiency of that use."[46]

The way that museums are planned and designed vary co-ordinate to what collections they firm, just overall, they adhere to planning a infinite that is hands accessed past the public and easily displays the called artifacts. These elements of planning have their roots with John Cotton Dana, who was perturbed at the historical placement of museums outside of cities, and in areas that were non hands accessed by the public, in gloomy European style buildings.[47]

Questions of accessibility continue to the present day. Many museums strive to make their buildings, programming, ideas, and collections more publicly accessible than in the by. Non every museum is participating in this trend, just that seems to be the trajectory of museums in the twenty-get-go century with its emphasis on inclusiveness. Ane pioneering manner museums are attempting to brand their collections more than attainable is with open up storage. Almost of a museum's collection is typically locked away in a secure location to be preserved, simply the upshot is nigh people never get to meet the vast majority of collections. The Brooklyn Museum's Luce Center for American Art practices this open up storage where the public can view items non on display, albeit with minimal estimation. The exercise of open up storage is all part of an ongoing fence in the museum field of the part objects play and how accessible they should be.[48]

In terms of modern museums, interpretive museums, equally opposed to art museums, have missions reflecting curatorial guidance through the bailiwick matter which now include content in the form of images, audio and visual furnishings, and interactive exhibits. Museum creation begins with a museum plan, created through a museum planning process. The process involves identifying the museum's vision and the resource, organization and experiences needed to realize this vision. A feasibility study, assay of comparable facilities, and an interpretive plan are all developed as part of the museum planning process.

Some museum experiences have very few or no artifacts and do not necessarily telephone call themselves museums, and their mission reflects this; the Griffith Observatory in Los Angeles and the National Constitution Center in Philadelphia, being notable examples where there are few artifacts, but potent, memorable stories are told or data is interpreted. In contrast, the The states Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. uses many artifacts in their memorable exhibitions.

Museums are laid out in a specific fashion for a specific reason and each person who enters the doors of a museum will run into its collection completely differently to the person behind them- this is what makes museums fascinating because they are represented differently to each individual.[49] : 9–10

Fiscal uses [edit]

In contempo years, some cities take turned to museums as an avenue for economic development or rejuvenation. This is specially true in the instance of postindustrial cities.[50] Examples of museums fulfilling these economic roles be effectually the earth. For example, the spectacular Guggenheim Bilbao was built in Bilbao, Espana in a motion by the Basque regional regime to revitalize the dilapidated old port area of that city. The Basque government agreed to pay $100 one thousand thousand for the construction of the museum, a price tag that caused many Bilbaoans to protest confronting the project.[51] Yet, the gamble has appeared to pay off financially for the city, with over ane.1 1000000 people visiting the museum in 2015. Key to this is the big demographic of foreign visitors to the museum, with 63% of the visitors residing outside of Kingdom of spain and thus feeding foreign investment straight into Bilbao.[52] A similar project to that undertaken in Bilbao was also congenital on the disused shipyards of Belfast, Northern Ireland. Titanic Belfast was built for the same price equally the Guggenheim Bilbao (and which was incidentally built by the aforementioned architect, Frank Gehry) in time for the 100th anniversary of the Belfast-built send's maiden voyage in 2012. Initially expecting modest visitor numbers of 425,000 annually, first twelvemonth visitor numbers reached over 800,000, with well-nigh sixty% coming from exterior Northern Republic of ireland.[53] In the United States, similar projects include the 81, 000 square pes Taubman Museum of Art in Roanoke, Virginia and The Wide Museum in Los Angeles.

Museums existence used as a cultural economic driver by metropolis and local governments has proven to be controversial amidst museum activists and local populations alike. Public protests have occurred in numerous cities which have tried to employ museums in this way. While most subside if a museum is successful, as happened in Bilbao, others continue specially if a museum struggles to attract visitors. The Taubman Museum of Art is an example of a museum which cost a lot (somewhen $66 million) but attained footling success, and continues to have a depression endowment for its size.[54] Some museum activists also see this method of museum use every bit a deeply flawed model for such institutions. Steven Conn, ane such museum proponent, believes that "to ask museums to solve our political and economic problems is to ready them up for inevitable failure and to set u.s. (the visitor) up for inevitable thwarting."[50]

Funding [edit]

Museums are facing funding shortages. Funding for museums comes from four major categories, and as of 2009 the breakdown for the United States is every bit follows: Government support (at all levels) 24.4%, individual (charitable) giving 36.v%, earned income 27.6%, and investment income eleven.5%.[55] Government funding from the National Endowment for the Arts, the largest museum funder in the U.s., decreased by 19.586 million between 2011 and 2015, adjusted for inflation.[56] [57] The boilerplate spent per visitor in an art museum in 2016 was $8 between admissions, store and restaurant, where the boilerplate expense per visitor was $55.[58] Corporations, which fall into the private giving category, can be a adept source of funding to make upwards the funding gap. The corporeality corporations currently give to museums accounts for just 5% of full funding.[59] Corporate giving to the arts, even so, was gear up to increment past iii.iii% in 2017.[threescore]

Exhibition design [edit]

Painting arranged in groupings 'Salon Style'

Well-nigh mid-size and large museums employ exhibit design staff for graphic and environmental design projects, including exhibitions. In addition to traditional 2-D and iii-D designers and architects, these staff departments may include audio-visual specialists, software designers, audience research, evaluation specialists, writers, editors, and preparators or fine art handlers. These staff specialists may too be charged with supervising contract design or production services. The exhibit design process builds on the interpretive program for an showroom, determining the most effective, engaging and appropriate methods of communicating a bulletin or telling a story. The process will often mirror the architectural procedure or schedule, moving from conceptual plan, through schematic design, design evolution, contract document, fabrication, and installation. Museums of all sizes may also contract the outside services of showroom fabrication businesses.[61]

Correct: 'Cabinet of curiosities' style of exhibit, ca.1890; Left: Contemporary history showroom, 2016

Some museum scholars have even begun to question whether museums truly need artifacts at all. Historian Steven Conn provocatively asks this question, suggesting that at that place are fewer objects in all museums now, every bit they take been progressively replaced by interactive technology.[62] As educational programming has grown in museums, mass collections of objects have receded in importance. This is not necessarily a negative development. Dorothy Canfield Fisher observed that the reduction in objects has pushed museums to grow from institutions that artlessly showcased their many artifacts (in the style of early cabinets of curiosity) to instead "thinning out" the objects presented "for a general view of any given discipline or period, and to put the rest away in archive-storage-rooms, where they could exist consulted by students, the only people who really needed to come across them".[63] This phenomenon of disappearing objects is especially present in science museums like the Museum of Scientific discipline and Industry in Chicago, which have a high visitorship of school-aged children who may benefit more than from hands-on interactive technology than reading a label beside an artifact.[64]

Types [edit]

The National Mall in Washington DC is home to diversity of museum types.

There is no definitive standard as to the gear up types of museums. Additionally, the museum landscape has become then varied, that information technology may not be sufficient to use traditional categories to cover fully the vast variety existing throughout the earth. However, it may be useful to categorize museums in unlike ways under multiple perspectives. Museums can vary based on size, from large institutions, to very small institutions focusing on a specific subjects, such as a specific location, a notable person, or a given period of fourth dimension. Museums too tin be based on the master source of funding: central or federal government, provinces, regions, universities; towns and communities; other subsidised; nonsubsidised and private.[65]

Information technology may sometimes exist useful to distinguish between diachronic museums - those that interpret the way in which its subject area matter has adult and evolved through fourth dimension (examples: Lower East Side Tenement Museum and Diachronic Museum of Larissa), and synchronic museums - those that translate the way in which its subject matter exists at one point in fourth dimension (examples:The Anne Frank House and Colonial Williamsburg). Co-ordinate to University of Florida'south Professor Eric Kilgerman, "While a museum in which a particular narrative unfolds within its halls is diachronic, those museums that limit their space to a single experience are called synchronic."[66]

In her book, Civilizing the Museum, author Elaine Heumann Gurian proposes that there are 5 categories of museums based on intention non content. Object Centered, Narrative, Client Centered, Community Centered, and National.[67]

Museums tin can also be categorized into major groups past the type of collections they display, to include: fine arts, applied arts, craft, archaeology, anthropology and ethnology, biography, history, cultural history, science, applied science, children'south museums, natural history, botanical and zoological gardens. Within these categories, many museums specialize further, due east.thou. museums of modern art, folk fine art, local history, military history, aviation history, philately, agriculture, or geology. The size of a museum'due south collection typically determines the museum'southward size, whereas its collection reflects the type of museum it is. Many museums normally display a "permanent drove" of important selected objects in its area of specialization, and may periodically display "special collections" on a temporary footing.[ citation needed ]

Major museum types [edit]

The following is a list to requite an thought of the major museum types. While comprehensive it is not a definitive list.

- Agricultural

- Architecture

- Archaeological

- Art

- Design

- Biographical

- Children's

- Community

- Encyclopedic

- Folk

- Celebrated business firm

- Historic site

- Living history

- Local

- Maritime

- Medical

- Memorial

- Natural history

- Open-air

- Science

- Virtual

Legal framework of museums [edit]

Public vs. private museums [edit]

Individual museums are organized by individuals and managed by a board and museum officers, but public museums are created and managed by federal, state, or local governments. A government can lease a museum through legislative action but the museum tin still exist private equally it is not office of the regime. The distinction regulates the ownership and legal accountability for the care of the collections.[38] [68]

Non-profit vs. for-profit museums [edit]

Nonprofit means that an organization is classified equally a charitable corporation and is exempt from paying most taxes and the money the organization earns is invested in the organization itself. Money fabricated by a individual, for-profit museum is paid to the museum's owners or shareholders.

The nonprofit museum has a fiduciary responsibility in regards to the public, in essence the museum holds its collections and administers it for the benefit of the public. Collections of for-turn a profit museums are legally corporate assets the museum administers for the benefit of the owners or shareholders.[38] [68]

Museums run by trusts vs. corporations [edit]

A trust is a legal musical instrument where trustees manage the trust's assets for the benefit of the museum following the specific wishes of the donor. This provides revenue enhancement benefits for the donor, and besides allows the donor to have command over how avails are distributed.

Corporations are legal entities and may acquire property in a way similar to how an individual can own property. Museums under incorporation are usually organized by a community or group of individuals. While a board of manager'due south loyalty is to the corporation, a board of trustee'southward loyalty has to be loyal to the intention of the trust. The ramification is that a trust is far less flexible than a corporation.[69] [70]

Current challenges facing museums [edit]

Sustainability and climatic change [edit]

Increasingly museums have been responded to the ongoing climate crisis through enacting sustainable museum practices, and exhibitions highlighting the issues surrounding climate change and the Anthropocene.

Decolonization of museums [edit]

Moai figure at the British Museum

During the beginning of the 21st century, a growing global movement for the decolonization of museums has arisen.[71] Proponents of this movement argue that 'museums are a box of things' and do non stand for complete stories; instead they show biased narratives based on ideologies, in which certain stories are intentionally disregarded.[49] : ix–18 Through this, people are encouraging others to consider this missing perspective, when looking at museum collections, as every object viewed in such environments was placed by an individual to stand for a certain viewpoint, be it historical or cultural.[49] : 9–eighteen

The 2018 report on the restitution of African cultural heritage [72] is a prominent instance regarding the decolonization of museums and other collections in France and the claims of African countries to regain artifacts illegally taken from their original cultural settings.

Since 1868, several monolithic human figures known as Moai accept been removed from Easter Isle and put in display in major Western museums such equally the National Museum of Natural History, the British Museum, the Louvre and the Royal Museums of Art and History. Several demands have been made by Easter Island residents for the return of the Moai.[73] The figures are seen as ancestors and family or the soul by the Rapa Nui and hold deep cultural value to their people.[74] Other examples include the Gweagal Shield, thought to be a very significant shield taken from Phytology Bay in Apr 1770[75] or the Parthenon marble sculptures, which were taken from Hellenic republic by Lord Elgin in 1805.[76] Successive Greek governments have unsuccessfully petitioned for the render of the Parthenon marbles.[76] Another example amongst many others is the then-chosen Montezuma'due south headdress in the Museum of Ethnology, Vienna, which is a source of dispute betwixt Austria and United mexican states.[77]

Laura Van Broekhoven, director of the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford, United kingdom, stated in 2020 that "ethnographic museums should redress their coloniality. They should be a pluriverse that shows the rich diverseness of ways of being and knowing, not centering whiteness equally the but fashion of beingness. Museums ought to let for everyone to empathize each other better."[78]

See too [edit]

-

Museums portal

Museums portal

- Sound tour

- Cell telephone tour

- Estimator Interchange of Museum Information

- Exhibition history

- Ennigaldi-Nanna's museum, world's kickoff museum

- International Council of Museums

- International Museum Mean solar day (18 May)

- Listing of museums

- List of largest art museums

- List of almost-visited museums

- List of near visited art museums

- List of most-visited museums by region

- .museum

- Museum pedagogy

- Museum fatigue

- Museum label

- Museum shop

- Public retention

- Scientific discipline tourism

- Types of museums

- Virtual Library museums pages

References [edit]

- ^ See Wiktionary definition, Collins English dictionary definition, Oxford English Dictionary definition

- ^ Edward Porter Alexander, Mary Alexander; Alexander, Mary; Alexander, Edward Porter (September 2007). Museums in motion: an introduction to the history and functions of museums. Rowman & Littlefield, 2008. ISBN978-0-7591-0509-six. Archived from the original on 13 April 2021. Retrieved 6 Oct 2009.

- ^ "How many museums are there in the world?". ICOM. 31 May 2018. Archived from the original on 4 December 2020. Retrieved 6 June 2019.

- ^ Findlen, Paula (1989). "The Museum: its classical etymology and renaissance genealogy". Journal of the History of Collections. ane (ane): 59–78. doi:10.1093/jhc/1.one.59.

- ^ Dunn, Jimmy. "Ptolemy I Soter, The First King of Aboriginal Egypt's Ptolemaic Dynasty". Bout Egypt. Archived from the original on four Oct 2019. Retrieved 5 April 2008.

- ^ "James Smithson Social club". Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on 20 October 2017. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- ^ Steven Conn, "Museums and American Intellectual Life, 1876–1926", 1998, The University of Chicago Press, 65.

- ^ Steven Conn, "Museums and American Intellectual Life, 1876–1926", 1998, The University of Chicago Printing, 262.

- ^ Babian, Sharon, CSTM: A History of the Canada Science and Applied science Museum, pp. 42–45

- ^ Lipschomb, Suzannah, "Historical Authenticity and Interpretive Strategy at Hampton Court Palace," The Public Historian 32, no.3, Baronial 2010, pp. 98–119.

- ^ "Museum Definition". International Quango of Museums. Archived from the original on 14 December 2021. Retrieved 12 December 2021.

- ^ Marshall, Alex (half-dozen Baronial 2020). "What Is a Museum? A Dispute Erupts Over a New Definition". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on eight August 2020. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

- ^ "Almost Museums - Clan of Manitoba Museums". www.museumsmanitoba.com. Archived from the original on 12 December 2021. Retrieved 12 December 2021.

- ^ "Eligibility". American Alliance of Museums. 25 Jan 2018. Archived from the original on 12 December 2021. Retrieved 12 December 2021.

- ^ "2 CFR § 3187.iii - Definition of a museum". LII / Legal Data Institute. Archived from the original on 12 December 2021. Retrieved 12 December 2021.

- ^ Wilkens, Alasdair (25 May 2011). "The story behind the world's oldest museum, built by a Babylonian princess 2,500 years ago". io9. Archived from the original on one April 2018. Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- ^ Manssour, Y. One thousand.; El-Daly, H. M.; Morsi, N. K. "The Historical Evolution of Museums Architecture" (PDF): 2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 January 2022. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

- ^ van Buren, E. Douglas (1922). "Museums and Raree Shows in Artifact". Folklore. 33: 337–53. Archived from the original on 7 November 2021. Retrieved 5 November 2021 – via JSTOR.

- ^ a b Genoways, Hugh; Andrei, Mary Anne, eds. (2008). Museum Origins: Readings in early on museum history and philosophy. Walnut Creek, California: Left Coast Press. pp. thirteen–15. ISBN978-1-59874-197-i.

- ^ "Museums in the Ancient Mediterranean". Globe History Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on five November 2021. Retrieved 5 November 2021.

- ^ Hubbell, H. M. (1935). "Ptolemy's Zoo". The Classical Journal. 31: 68–76. Archived from the original on 5 November 2021. Retrieved 5 Nov 2021 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Chang Wan-Chen, A cantankerous-cultural perspective on musealization: the museum's reception by China and Japan in the second one-half of the nineteenth century in Museum and Order, vol ten, 2012.

- ^ Paula Findlen, Possessing Nature: Museums, Collecting, and Scientific Civilization in Early on Modern Italy (Berkeley, California: Academy of California Press, 1994),3.

- ^ Paula Findlen, Possessing Nature: Museums, Collecting, and Scientific Civilisation in Early Modern Italia (Berkeley, California: Academy of California Press, 1994),62.

- ^ Paula Findlen, Possessing Nature: Museums, Collecting, and Scientific Culture in Early on Modern Italian republic (Berkeley, California: University of California Press, 1994),393–397.

- ^ The British Museum, " Admission Ticket to the British Museum" https://world wide web.britishmuseum.org/explore/highlights/highlight_objects/archives/a/admission_ticket_to_the_britis.aspx Archived 13 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine, accessed iv/iii/fourteen.

- ^ "History of the British Museum". British Museum. Archived from the original on 12 April 2012. Retrieved 15 June 2017.

- ^ Swann, Marjorie (2001), Curiosities and Texts: The Culture of Collecting in Early Modern England, Philadelphia: Academy of Pennsylvania Press

- ^ H. E. Salter and Mary D. Lobel (editors) Victoria County History A History of the County of Oxford: Book iii 1954 Pages 47–49 Archived 8 February 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "History of Louvre". History of Louvre. Archived from the original on 24 October 2013. Retrieved 14 Nov 2013.

- ^ Chang Wan-Chen, A cross-cultural perspective on musealization: the museum's reception by China and Nihon in the second half of the nineteenth century in Museum and Society, vol. 10, 2012.

- ^ Bennett, Tony (1995). The Birth of the Museum. New York: Routledge Press. pp. 6, 8, 24. ISBN0-415-05388-ix.

- ^ Gulliford, Andrew (1992). "Curation and Repatriation of Sacred and Tribal Artifacts". The Public Historian. 14 (3): 25. doi:10.2307/3378225. JSTOR 3378225.

- ^ "The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Deed (NAGPRA)". National Park Service. Archived from the original on 21 Apr 2016. Retrieved 18 April 2016.

- ^ Duthie, Emily (2011). "The British Museum: An Majestic Museum in a Post-Imperial Earth". Public History Review. 18: 12–25. doi:10.5130/phrj.v18i0.1523.

- ^ American Association of Museums, "The Accreditation Commission's Expectations Regarding Governance." p. 1. Archived nineteen November 2011 at the Wayback Auto

- ^ a b Hugh H. Genoways and Lynne M. Ireland, Museum Administration: An Introduction, (Lanham: AltaMira, 2003), 3.

- ^ a b c Latham, Kiersten F.; Simmons, John E. (2014). Foundations of Museum Studies: Evolving Systems of Noesis Illustrated Edition. Libraries Unlimited. p. ix. ISBN978-1610692823.

- ^ Pierce, Dennis (November–December 2018). "The Quest for Excellence: Small museums really do have the resources to pursue accreditation" (PDF). Museum. American Alliance of Museum: 16–26. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 December 2021. Retrieved 12 December 2021 – via American Alliance of Museum.

- ^ Roberts, Lisa C. (1997). From Knowledge to Narrative: Educators and the Changing Museum. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Establishment Press. p. 2.

- ^ Academy of Rochester, "Museum Job Descriptions". Archived five April 2012 at the Wayback Motorcar

- ^ Cf. e.g. Marilyn E. Phelan: Museum Law: A Guide for Officers, Directors, and Counsel. 2014, p. 419 ff.

- ^ "ICOM and the International Commission of the Blue Shield". ICOM. Archived from the original on 23 March 2020.

- ^ Peter Stone Inquiry: Monuments Men. In: Apollo – The International Art Mag. ii February 2015; Mehroz Baig: When War Destroys Identity. In: Worldpost. 12 May 2014; Fabian von Posser: Welterbe-Stätten zerbombt, Kulturschätze verhökert. (German) In: Die Welt. five Nov 2013.

- ^ Dana, John Cotton. The New Museum (Woodstock, VT: The Elm Tree Press, 1917), 25.

- ^ Dana, John Cotton fiber. The New Museum (Woodstock, VT: The Elm Tree Press, 1917), 32.

- ^ Dana, John Cotton. The Gloom of the Museum. (Woodstock, VT: The Elm Tree Press, 1917), 12.

- ^ "Turning Museums Inside-Out with Cute Visible Storage". Atlas Obscura. 24 September 2014. Archived from the original on ane Feb 2016. Retrieved one February 2016.

- ^ a b c Procter, Alice (2020). The whole Picture: the colonial story of the art in our museums and why we need to talk nearly information technology. England: Cassel. ISBN978-1-78840-221-7.

- ^ a b Conn, Steven (2010). Practice Museums Nonetheless Need Objects?. Philadelphia: Academy of Pennsylvania Press. p. 17.

- ^ Riding, Alan (24 June 1997). "A Gleaming New Guggenheim for Grimy Bilbao". The New York Times. p. C9.

- ^ "Guggenheim Bilbao Almanac Report 2015" (PDF). Guggenheim Bilbao. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 Jan 2016. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ^ Smyth, Jamie (sixteen June 2013). "Northern Ireland Focus: Titanic Success Raises Hopes For Tourism". Financial Times.

- ^ Wallis, David (20 March 2014). "Offset-Up Success Isn't Enough to Found a Museum". The New York Times. p. F6.

- ^ Bell, Ford W. "How Are Museums Supported Nationally in the U.S.?" Archived 10 Oct 2018 at the Wayback Motorcar Embassy of the U.s. of America, 2012.. Accessed 26 March 2017.

- ^ "National Endowment for the Arts 2011 Annual Written report." Archived x January 2019 at the Wayback Motorcar National Endowment for the Arts, 2012. Accessed 26 February 2017.

- ^ "National Endowment for the Arts 2015 Annual Written report." Archived 11 January 2019 at the Wayback Machine National Endowment for the Arts, 2016.. Accessed 26 February 2017.

- ^ Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD) Archived xix December 2018 at the Wayback Automobile, "Art Museums by the Numbers 2016." AAMD.org,. Accessed 26 February 2017.

- ^ Stubbs, Ryan and Henry Clapp. "Public Funding for the Arts: 2015 Update." Archived 26 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine Grantmakers in the Arts, GIA Reader, vol. 26, no. 3, Autumn 2015.. Accessed 26 February 2017.

- ^ "Sponsorship Spending on the Arts to Grow 3.3 Percent in 2017". ESP Sponsorship Report. ESP Properties, LLC. xiii Feb 2017. Archived from the original on 15 March 2018. Retrieved fifteen March 2018.

- ^ Taheri, Babak; Jafari, Aliakbar; O'Gorman, Kevin (2014). "Keeping your audition: Presenting a visitor date scale" (PDF). Tourism Direction. 42: 321–329. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2013.12.011. Archived (PDF) from the original on eleven November 2021. Retrieved twenty November 2018.

- ^ Conn, Steven (2010). Exercise Museums Even so Need Objects?. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Printing. p. 26.

- ^ Canfield Fisher, Dorothy (1927). Why Finish Learning?. New York: Harcourt. pp. 250–251.

- ^ Conn, Steven (2010). Do Museums Still Need Objects?. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 265.

- ^ Ginsburgh, Victor; Mairesse, François (1997). "Defining a Museum: Suggestions for an Alternative Arroyo". Museum Management and Curatorship. Routledge. xvi: fifteen–33.

- ^ Kilgerman, Eric. Sites of the Uncanny: Paul Celan, Specularity and the Visual Arts Archived 8 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine, p. 255 (2007).

- ^ Heumann Gurian, Elaine (17 May 2006). The Collected Writings of Elaine Heumann Gurian. Taylor & Francis. pp. 48–56.

- ^ a b Malaro, Marie C.; DeAngelis, Ildiko (2012). A Legal Primer on Managing Museum Collections, Third Edition. Smithsonian Books. p. 8. ISBN978-1588343222.

- ^ Latham, Kiersten F.; Simmons, John E. (2014). Foundations of Museum Studies: Evolving Systems of Knowledge Illustrated Edition. Libraries Unlimited. p. 11. ISBN978-1610692823.

- ^ Malaro, Marie C.; DeAngelis, Ildiko (2012). A Legal Primer on Managing Museum Collections, 3rd Edition. Smithsonian Books. pp. 6–ix. ISBN978-1588343222.

- ^ Brennan, Bridget (10 May 2019). "The battle at the British Museum for a 'stolen' shield that could tell the story of Helm Cook's landing". ABC News (Australian Broadcasting Corporation). Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- ^ Felwine Sarr, Bénédicte Savoy: "Rapport sur la restitution du patrimoine culturel africain. Vers une nouvelle éthique relationnelle". Paris 2018; "The Restitution of African Cultural Heritage. Toward a New Relational Ethics" (Download French original and English version, pdf, http://restitutionreport2018.com/ Archived fifteen Baronial 2021 at the Wayback Auto

- ^ Bartlett, John (xvi November 2018). "'Moai are family unit': Easter Island people to caput to London to request statue dorsum". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 22 December 2020. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- ^ Bartlett, John (16 November 2018). "'Moai are family': Easter Island people to caput to London to asking statue dorsum". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 22 Dec 2020. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- ^ Thomas, Nicholas (2018). "A Instance of Identity: The Artefacts of the 1770 Kamay (Botany Bay) Encounter". Australian Historical Studies. 49:i: 4–27. doi:x.1080/1031461X.2017.1414862. S2CID 149069484. Archived from the original on 25 February 2022. Retrieved fourteen September 2020 – via ResearchGate.

- ^ a b "How the Parthenon Lost Its Marbles". History Mag. 28 March 2017. Archived from the original on 2 February 2021. Retrieved eight February 2021.

- ^ "Mexico and Austria in dispute over Aztec headdress". prehist.org. 22 Nov 2012. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 24 Nov 2012.

- ^ Settler Colonialism, Slavery, and the Trouble of Decolonizing Museums (sixteen December 2020). "Keynote Speaker". decolonizingmuseums.com. Archived from the original on 21 October 2021. Retrieved 21 Oct 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Further reading [edit]

- Bennett, Tony (1995). The Birth of the Museum: History, Theory, Politics. London: Routledge. ISBN978-0-415-05387-7. OCLC 30624669.

- Conn, Steven (1998). Museums and American Intellectual Life, 1876–1926. Chicago: The University of Chicago Printing. ISBN0-226-11493-7.

- Cuno, James (2013). Museums Matter: In Praise of the Encyclopedic Museum. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. ISBN978-0-226-10091-3.

- Findlen, Paula (1996). Possessing Nature: Museums, Collecting, and Scientific Civilization in Early Modern Italian republic. Berkeley: University of California Printing. ISBN0-520-20508-i.

- Marotta, Antonello (2010). Contemporary Milan. ISBN978-88-572-0258-7.

- Murtagh, William J. (2005). Keeping Time: The History and Theory of Preservation in America. New York: Sterling Publishing Visitor. ISBN0-471-47377-4.

- Rentzhog, Sten (2007). Open up air museums: The history and future of a visionary idea. Stockholm and Östersund: Carlssons Förlag / Jamtli. ISBN 978-91-7948-208-4

- Simon, Nina K. (2010). The Participatory Museum. Santa Cruz: Museums 2.0

- van Uffelen, Chris (2010). Museumsarchitektur (in High german). Potsdam: Ullmann. ISBN978-3-8331-6033-2. – also bachelor in English: Gimmicky Museums – Architecture History Collections. Braun Publishing. 2010. ISBN978-3-03768-067-4.

- Yerkovich, Sally (2016). A Applied Guide to Museum Ethics. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN978-one-4422-3164-ane.

- "The Museum and Museum Specialists: Issues of Professional Education, Proceedings of the International Briefing, 14–fifteen Nov 2014" (PDF). St. petersburg: The Land Hermitage Publishers. 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on x May 2017. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

External links [edit]

-

Media related to Museums at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Museums at Wikimedia Commons - International Quango of Museums

- Museums of the World

- VLmp directory of museums

- Museums at Curlie

manningablightmed.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Museum

0 Response to "Living American Art Collotype No 78 Reproduced by Courtesy of Bartlett Arkell"

Post a Comment